I’m getting ready to teach at a sewing retreat in August, so I’ve had my head down this summer making lesson plans, class handouts, and sewing samples. Next week, I’ll circle up with 36 other makers in a cabin deep in the Maine woods, and we’ll talk about my favorite subject in the whole world: making pants.

Learning how to make a pair of pants involves a variety of different skills, but the one I’ll focus on next week is arguably the biggest: fitting. Customizing a 2-dimensional sewing pattern to fit the unique 3-dimensional shape of the maker’s body, aka “fitting”, is a separate skillset from the physical garment construction, and it’s an important one for anyone who wants to make pants that are comfortable, functional, and fabulous.

Out of all the items in our closets, pants have a reputation for being the most challenging type of garment to fit. Fitting pants usually conjures strong emotions among sewists: fear, dread, frustration, and anxiety.

There are many reasons for this angst. Creating a bifurcated garment that looks good, feels comfortable, and performs well under all of the mechanical stresses throughout the day is no small feat. Pants often require advanced construction techniques like a zipper fly, a waistband, or top stitching, and they are made with heavyweight fabrics like denim or canvas that require more skill to manipulate. Pants must also traverse the most physically and emotionally sensitive parts of the body, which adds a complicated psychological component for many of us.

But none of that is what I want to write about today. There’s a different reason why fitting pants can feel so hard to master, and it’s been on my mind as I prepare to teach a fitting workshop. It might come as a surprise, but this reason has nothing to do with pants or with body shapes. It’s the teaching methods. The way that most experts talk about and teach fitting classes is outrageously misaligned with best practices for teaching a skill. They are setting students up to fail, and we aren’t talking about it enough in the sewing community.

The problem with perfect

Open up any popular fitting guide and you’re likely to see the same paradigm taught again and again. Most fitting resources teach us that our goal should be to achieve the “perfect" fit on every garment we make. The idea that we should all be striving to be perfect while fitting is so ubiquitous that it’s written on the cover of dozens of popular fitting books. Here is a just small selection:

The same is true for many in-person fitting classes and workshops. Lately I’ve been relentlessly targeted by Instagram ads for a fitting masterclass from the self-proclaimed Queen of Fitting. Here’s her opening line in the ad (emphasis mine):

“Do you love making garments but HATE getting the fit WRONG? I’ll teach you how to get the PERFECT fit on all your patterns before you even cut your fabric.”

Here we are being prompted to feel strong, negative emotions (hatred! wtf!?) when an outcome doesn’t match our expectations, which by the way is a very normal and common occurrence when we are learning a new skill. We are also being conditioned to expect perfection on the very first step of the process — before even cutting fabric or trying on a toile.

Let’s set aside the fact that most of these resources define “perfect fit” so narrowly that it’s impossible to achieve with many styles of pants. Or that the tools taught to us in these books and classes are never fully explained, so we don’t develop an understanding of how or why they work and what trade-offs we must accept when we choose one strategy over another. I’ll save that for another newsletter.

Fitting pants is a complex skillset involving spatial reasoning, critical thinking, and problem solving, none of which are compatible with perfectionism. When teaching a complex skill, regardless of the subject matter, indoctrinating students to desire perfection from the moment they step foot in the classroom or open a textbook is not only an ineffective teaching strategy, it’s also a cruel one.

Practice over perfection

What none of these fitting resources seems to understand is that when students are instructed to achieve a “perfect” outcome during the learning process, they quickly become afraid of making mistakes or getting things “wrong”. Making mistakes is an essential part of how we learn new skills. Think back to the last time you had to learn a complex skill set from scratch — was it realistic or productive to expect that you’d be perfect on the first try? Probably not!

When we fixate on creating a perfect outcome, we begin to think in a harsh binary: either the outcome will be perfect, or it will be a failure. Any flaws in our work, no matter how minor, dooms the entire effort. And because no one likes failing repeatedly, it is much easier to quit and write off our learning goals as impossible when we have a string of perceived failures. When we stop trying, we can’t learn.

The best strategy to learn how to fit pants is not to pursue perfection, it’s to pursue practice. Combined with things like curiosity and reflection, practice is the key to mastering any skill. Fitting pants is no exception.

Here’s a great video from one of my creative heroes, Julia Child, talking about the value of practice when learning new skills, in this case flipping a big pan of potatoes:

She says in the video after she fumbles the flip:

“The only way you learn how to flip things is just to flip them.”

And then she covers her mistakes in cheese and cream. A woman after my own heart!

The lesson here works for flipping potatoes as it does for fitting pants: The only way we learn a new skill is to practice it. Sometimes the outcome of our hard work doesn’t match our expectations, even for the pros. But there is always something to be gained from the experience, so we keep going and learn along the way.

Centering practice instead of perfection also opens the door for a much more enjoyable learning experience. Students who are focused on process instead of outcomes are more engaged and curious. Emphasizing practice also allows us to be more compassionate toward ourselves as we are learning, because we get an infinite number of do-overs if something doesn’t work out the way we wanted at first. With more engagement, curiosity, and compassion, learning becomes more enjoyable. And when we are enjoying ourselves, we tend to learn faster.

Perpetuating perfection

Using teaching strategies that make learning easier and more enjoyable—and avoiding the ones that don’t—seems like a no brainer to me. So I’m left with one question: why? Why do we keep teaching perfectionism in fitting when it is obviously an ineffective way to learn?

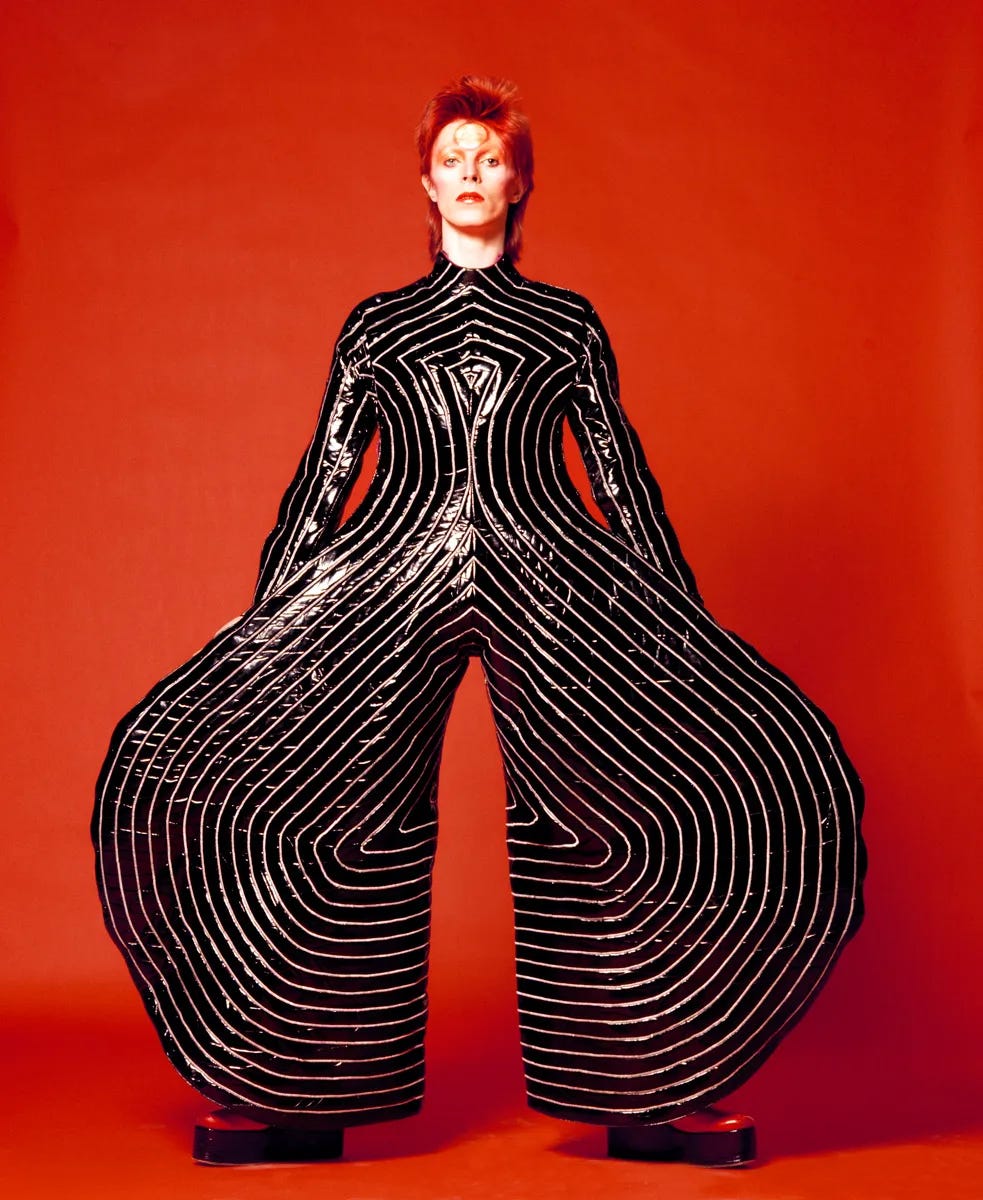

It’s fairly rare to encounter such a fixation with perfect outcomes in other creative pursuits1. For example, the idea of teaching students to paint the perfect landscape or carve a perfect sculpture is absurd. “Perfect” has no meaning in creative disciplines where the work can be as varied and diverse as the human imagination. I’d argue that trying to achieve the perfect fit on a pair of pants is no different; the way pants look and fit the human body is limited only by our own creativity and individual preferences, and we all know that there are no rules in fashion. So why are we so fixated on the “perfect fit”?

When I try to answer this question, I think about how the fitting rhetoric is still closely tied to traditional (and harmful) ideas about the perfect body. So many popular fitting books are littered with references to the ideal figure and how we should all want one of those, too. To get the perfect fit, we are instructed to first compare ourselves to the perfect body and find the differences, then adjust the pattern for those offending body parts. What is implied, insidiously: our imperfect bodies are a problem to be solved. We cannot keep perpetuating this message.

Some recent fitting guides have tried to tone down or even remove the language about ideal figures and perfect body shapes, but they haven’t let go of teaching perfectionism or body part adjustments. Their message is “you can get the perfect fit no matter what size or shape your body takes.” I admire that these teachers are finally starting to reject harmful and outdated ideas about idealized body shapes, but it is not enough.

My issue is that you can’t have one without the other; the quest for a perfect fit is a veiled extension of the desire for a perfect body. In both cases, a set of arbitrary rules tells us what is “right” and “wrong” about how we present ourselves to the world, and we are encouraged to scrutinize our appearance to find flaws. These are classic systems of oppression, largely against those who identify as women, and force us to center our lives around physical appearance and performance for others. We must reject all of them.

A new paradigm for learning to fit

It is high time for a new paradigm for how we teach sewists to fit garments. Instead of teaching perfectionism, I want fitting resources that encourage learning through practice, experimentation, and reflection. I want to see teaching strategies that focus on developing skills like problem solving and critical thinking, equipping makers with the actual tools we need for a deeper understanding of how a flat pattern piece becomes a 3-dimensional garment and creates the fit.

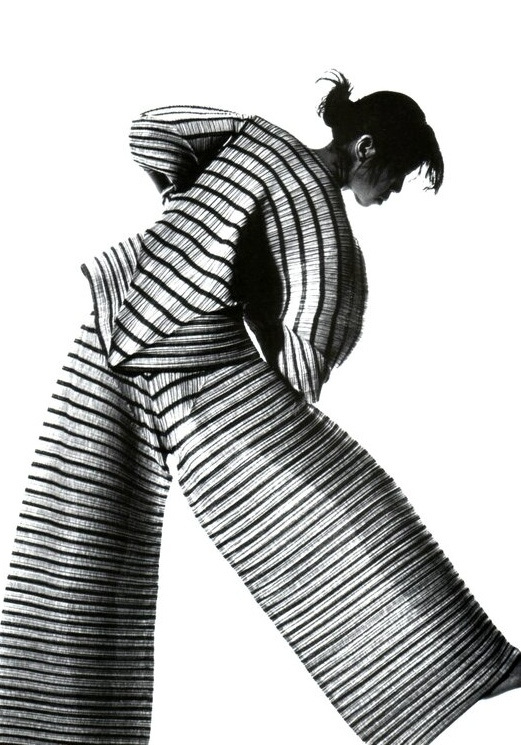

In parallel, we need to change how we talk about what fit actually is. The “perfect fit” is often viewed as a single, immutable thing, where every parameter and measurement on a pattern is somehow “correct”, leading to a flawless, magical garment. This is absurd. We need a more nuanced discussion of what fit actually is and all of the different ways it can vary. Fit is never one single thing, it is a spectrum of many variables. It is dynamic and changes depending on the garment style, fabric choice, and body movements of the wearer.

Finally, I want to see us move away from conventional fitting approaches based in harmful patriarchal systems. We need to teach alternatives that don’t require makers to identify problematic body parts or judge their bodies against an ideal standard. Luckily, we already have such a method. If you’ve followed me on other platforms, then you know that I am a huge proponent of a body neutral approach for fitting pants (aka Top Down Center Out), and this method is what I will teach next week in Maine.

I’m hoping that I can be the change I want to see, so my lesson plan for next week will emphasize skills like how to make decisions while fitting, how to isolate variables when problem solving, and how to incorporate reflection and practice to see improvements. I’ve also removed the word “perfect” from my fitting vocabulary, and I will encourage my students to try doing the same.

When I started writing this newsletter, I didn’t think it would end in a fitting manifesto, but here we are. If this newsletter resonated with you, let me know in the comments, I’d love to start a conversation.

As always, thank you for being here and for reading.

—Stacey

P.S. - I’ve been lucky to find several exceptional teachers who emphasize practice, experimentation, curiosity, compassion, joy, and problem solving in their classrooms. Take a class with them if you’re able to or give them a follow.

Learn all the things:

Lindsay Stripling - an artist, illustrator, teacher, and fellow Substack author. I recently took Lindsay’s Yellow Brick Road class, which focuses on guiding students to find their creative voices and make art that is more personally meaningful. Lindsay’s classes emphasize the value of self-compassion, self-exploration, joy, and practice. I am taking Lindsay’s color class later this month, sign ups are still open (wink, wink).

Eira Adeli - a pattern maker, sewist, and teacher. Eira’s classes are packed full of information about construction techniques, sewing tools, pattern making, and more. I’ve taken two classes with Eira focusing on garment construction, and she models how to be curious, experiment, and problem solve. You are guaranteed to level up your skills with any class Eira teaches.

Ruth Collins - a sewist, inventor, teacher, and Substack author. Ruth created the Top Down Center Out method and is the inspiration behind just about everything I post online about fitting, including this newsletter. Her fitting philosophies are grounded in the scientific method, and she helped me develop a deeper understanding of how patterns create fit (among many other things). I’m honored to call her my friend and fitting mentor.

The idea of perfection does show up when we consider creative disciplines with a performance element, although I would argue that we don’t usually see perfectionism show up until students reach elite skill levels. A flawless performance can have a place in the art world: a principal violin concerto, an olympic gymnastic routine, a prima ballerina’s solo. Do we accept and perpetuate the “perfect fit” rhetoric because fitting is ultimately a performative act? Dressing ones self is a performance, after all — for ourselves and for others.

Thanks for sharing! Pants are a great example; to me there is no "perfect fit" even if I think I know what I'm aiming for. Are these pants for standing, sitting, or moving? Are they keeping me warm or cool? Do I need the hem to stay out of my bike chain? What shape and size is my body compared to last week (or this morning)? Chances are I'm doing some combination of those things while navigating by own body variability, and the same pant made 12 different ways (with different fabrics) will excel in different categories. I've definitely been disappointed with fit after making pants only to pick them up later when circumstances change. I've changed the way I think about fit too in terms of what the wearer wants, and notice much more the coded language that gets used to describe fit (like "slimming" and "flattering").

Stacey, what you have written feels revolutionary but shouldn’t be. You have called out many nefarious systemic issues in our “hobby”. Kudos.